This essay was adapted from an article I wrote for Whetstone Volume 7 in 2021. For the full piece, you can purchase the magazine here.

In Taiwanese cuisine, oysters are never eaten raw and they don’t often show up in fancy restaurants. Yet they are one of the most widely used ingredients in the broad canon of Taiwanese cuisine. “In Taiwan, oyster farming is not considered a fine industry,” Huang Yi-cheng 黃翊誠, an oyster farmer off the coast of Qigu, Taiwan, tells me. I meet Huang on his oyster farm. He’s a bespectacled man with solid black-rimmed glasses, tall, scrawny, and notably young. Known as the Oyster Man, Huang is an outlier in an industry where the average age is 60 years or above. His farm is a patchwork of still water by the bay, with green meshed nets and a small wooden canoe for transportation.

There’s a run-down bamboo shack at the edge for storage. His only coworkers are his aging parents, who are still out on the water daily, harvesting oysters underneath the hot, beating sun. There is nothing glamorous about their line of work. The oysters are grown on rows of floating bamboo, buoyed up by thick slabs of Styrofoam and tied down with strings of empty oyster shells. The empty shells are a substrate for the microscopic oyster larvae to grow on.

The art of oyster farming was brought over to Taiwan more than 200 years ago by Chinese immigrants. While there have been some mild advancements—like the Styrofoam blocks to help oyster racks stay afloat—most things have stayed unchanged. Traditionally, an oyster farm consisted of empty oyster shells tied on sticks surrounded by shallow brackish water. Many aquaculture farmers in Taiwan today still use this basic system, but the primitive nature of the industry in Taiwan means that most local oysters cannot be eaten raw because in order for that to happen, the surrounding water quality has to be monitored religiously. A single adult oyster can filter as much as 50 gallons (225 L) of water a day, but because they are natural filtration systems, they are also sensitive to pollutants in the water. “The oyster is a powerful living creature,” Huang, who has a bachelor’s in aquaculture and a master’s in fisheries science, tells me. “In a polluted environment, oysters can take in toxins.” In Taiwan, most oyster farmers lack the infrastructure and knowledge to stay on top of their water quality—a major shortcoming of the industry and why the mollusk is so undervalued.

“You have to use data to prove to consumers that your oysters are safe,” Huang says. As a trained scientist, he insists on testing his own oysters on his own farm, and sends samples to labs on a regular basis for quality control. He hopes that one day his peers will follow his example, and that the Taiwanese oyster industry will prioritize quality over quantity. “The profit margins are not great, and so of course, people will choose the cheapest way to raise them,” he says.

At the end of my tour, Huang hands me a freshly harvested, shucked oyster—giant and almost luminescent in the early morning sun. He brags that it’s so fresh that its heart is still beating.

“Do you dare?” he asks.

I slurp it down, and wince at how warm it is. I’m used to oysters served on ice, not pulled straight from a warm, subtropical bay. At first all I get is salt, but then the aftertaste comes creeping in—a delicate, soft sweetness that tastes exactly like fresh watermelon. Despite decades of eating blanched or deep-fried Taiwanese oysters, this comes as a complete surprise to me.

“Like watermelon right?” Huang beams. “I have no idea why. It’s the strangest thing.”

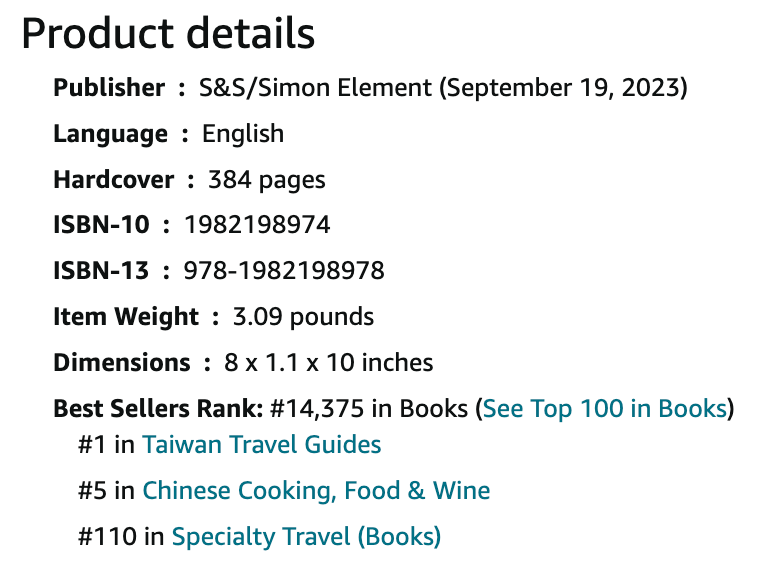

It’s one more month until my cookbook MADE IN TAIWAN: RECIPES AND STORIES FROM THE ISLAND NATION launches and every day I obsessively check how my book is tracking on Amazon, which is probably not the most healthy of habits.

The build-up before releasing a book is unlike anything I’ve ever experienced before. As a freelance journalist, I usually expend most of my energy pitching, researching, and writing. Once an article is filed and published, I’ll tweet about it and move on.

This is another beast. I think of launch day like a tidal wave and my job right now is to build up momentum. The bigger that wave is, the more people will talk about it, the more publications will cover it, and the more sales I might get. Every debut author wants to make a splash because a big splash means future book deals (👋 hello income stability) and a chance to earn out the advance sooner than…never (FYI, the majority of authors never earn out their advance).

This is why pre-orders are so important for authors.

Sometimes I get messages from people who ask what’s the best way to support me and if they can buy the book directly from me (no I’m not a bookseller and I don’t have stock). The truth is, it doesn’t really matter where you buy the book, though I’d genuinely appreciate it if you supported indie bookstores instead of the giant online retailers. It’s more the timing that matters because pre-orders count toward first-week sales. The more sales in a week, the higher the chance an author has of hitting a bestseller list.

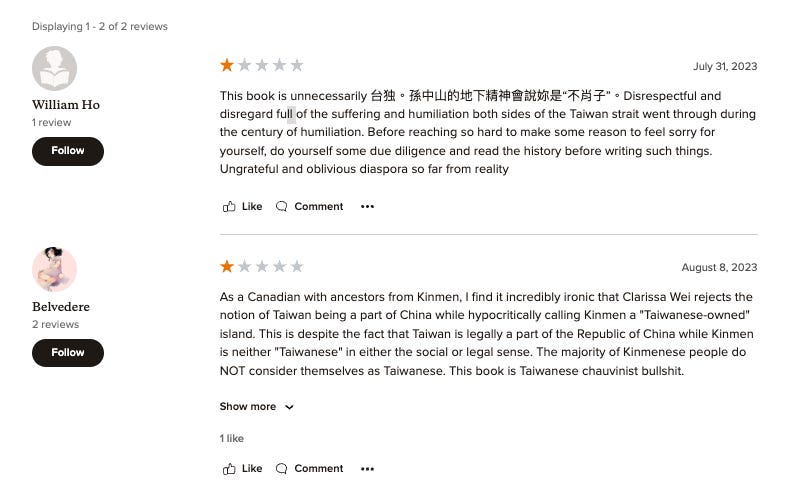

With that said, I’ve been getting interesting feedback already on Goodreads…

Because the book is not out yet, I assure you that these reviews are not based on anything except for the premise of my book: That Taiwanese food is its own unique genre. One that is separate from that of China.

There are only two bad reviews on here (some supporters logged on and decided to help cancel that out by giving me 5-star reviews, to which I say thank you, but you’re totally welcome to rate me after you’ve read the book), but their animosity reflects the type of messaging I get bombarded with on a semi-regular basis on my social media channels. I’ve had to block literally thousands of CCP trolls over the last couple of years to stop the harassment. Thank goodness for Blockparty (…which now does not work under Musk).

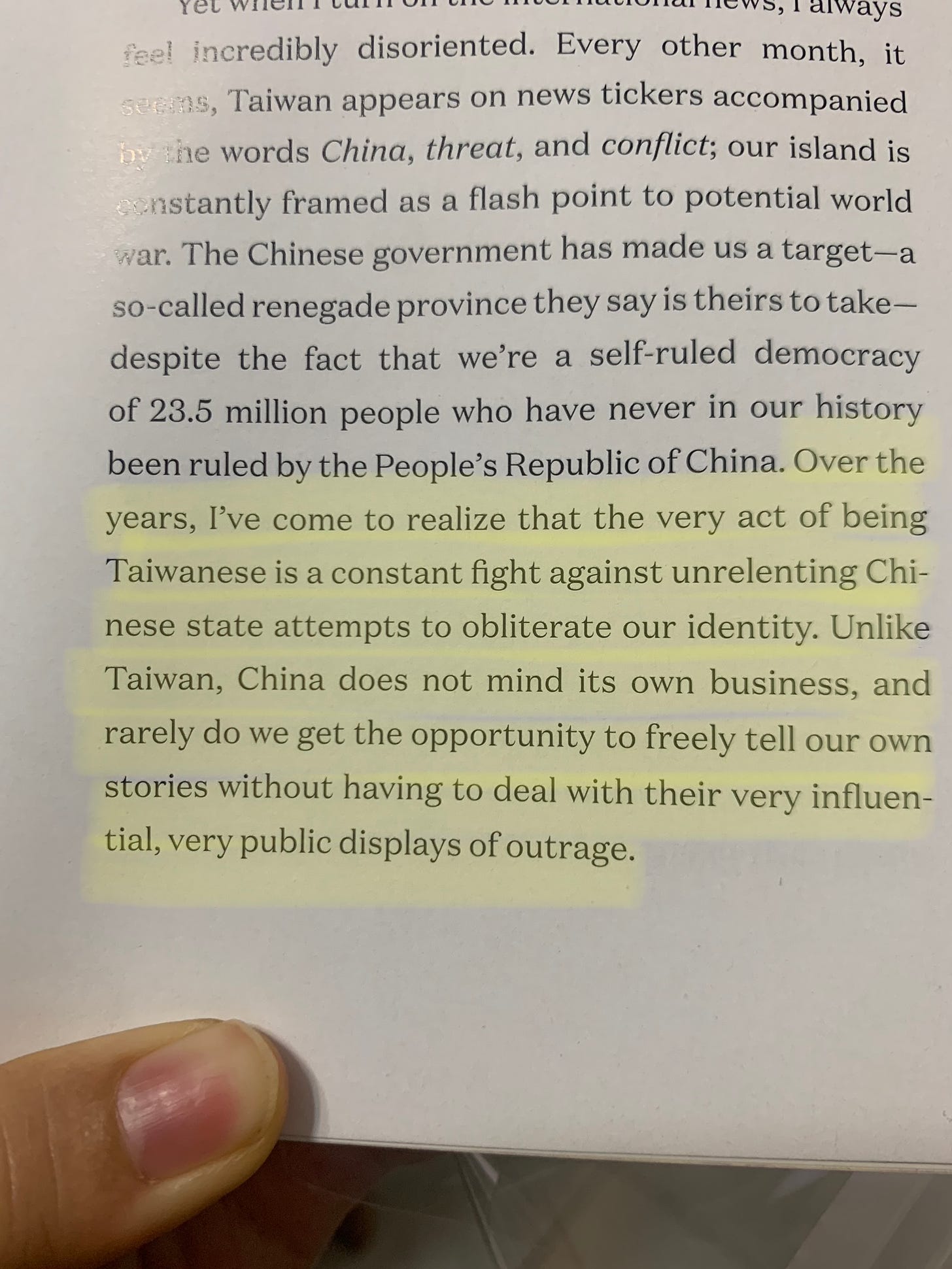

This is the reality of being Taiwanese these days. In fact, I’ve been so cognizant of this type of disparaging rhetoric that I wrote about it in my book:

It’s unfortunate that these types of comments happen, but it’s also why I wrote this cookbook with the politics of Taiwan in mind. As the NYTimes reporter Li Yuan wrote in a wonderful recent article on what cuisine means to Taiwan’s identity: “Nowhere does food exist independently from politics.”

Virtual Book Tour

As I mentioned in my previous newsletter, my book tour this fall will mostly be virtual, with a couple of IRL events in Taipei in November. Would love to see you guys online! Here’s a pending list of events. I keep an updated list on my website.

Smithsonian Book Launch (VIRTUAL)

September 19, 2023

🕒 6:45 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. EST

Wei discusses the flavorful cuisine of Taiwan—and what makes it distinctive in Asian cooking—in a conversation with Esther Tseng, a food, drinks, and culture writer.

The Ruby (VIRTUAL)

October 17, 2023

🕒 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. PST

Join us in celebrating the release of Clarissa Wei's debut cookbook, MADE IN TAIWAN! Clarissa will be joined by Soleil Ho in conversation. As an added bonus, we are honored to host a cooking demo with Clarissa and MADE IN TAIWAN recipe developer, Ivy Chen!

Taipei Foreign Correspondents’ Club Book Talk (TAIPEI)

November 8, 2023

🕒 TBD Taipei Time

🏡 Red Room Rendezvous 紅房餐酒館

Members only. RSVP details to be announced.

New Bloom Book Signing and Panel (TAIPEI)

November 18, 2023

🕒 TBD Taipei Time

🏡 Daybreak 破曉咖啡 (New Bloom 破土)

In-person book signing and conversation with the entire cookbook team. RSVP details to be announced.

What I’ve Been Working On + Buzz

For Foreign Policy, I wrote a review of Netflix’s Wave Makers. It’s a Taiwanese political drama about a motley group of campaign staffers months away from a decisive presidential election. And yes, there are English subtitles (though they often miss the mark). "Wave Makers lacks the witty banter of great political thrillers. But if you’re able to overlook predictable plot turns and a syrupy sweet script, the show offers a clear porthole into the unique culture of modern Taiwanese politics. At its core, it is a celebration of one of the main features of a healthy democracy: the ability of regular citizens to hold those in power accountable.”

MADE IN TAIWAN is also starting to get its first batch of press. We were featured in this month’s issue of Food and Wine magazine, got a nod in Publishers Weekly, and were reviewed in Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Magazine.

That’s it for now! Thanks for reading.